The current US administration has clearly adopted an anti-Iranian strategy that is not limited to rhetoric but also includes putting pressure on its allies to assist in isolating Iran.

Prince Tamim of Qatar gave a speech last week thanking the countries that opened air space for Qatari planes, without mentioning Iran. We also saw the recent Kuwaiti diplomatic crisis with Iran, which resulted in the expulsion of the Iranian ambassador and 14 other diplomats for alleged links to a spy and terror cell. The US President has also asked Sultan Qaboos of Oman to help contain Iran’s influence in the region, and observers are carefully witnessing the Saudi attempts to open a dialogue with Iraq as a further attempt to contain Iranian influence.

This coordinated effort is not limited to Iran, but also to its key allies. Recently we saw the US anti-Hezbollah rhetoric reappear as U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Nikki Haley urging the U.N. Security Council to acknowledge that Hezbollah “is a destructive terrorist force” and “a major obstacle to peace” that is “dedicated to the destruction of Israel.” This rhetoric harks back to the 2005-2008 policies that targeted the Lebanese party and preceded the July 2006 war against Hezbollah.

This new approach was also seen during the Lebanese Prime Minister Saad Al Hariri’s last visit to Washington and his meeting with President Trump. The likely goal is to isolate Hezbollah and put more pressure on them as new agreements and understandings are being negotiated in Syria.

According to the US National Security Report, Hezbollah has not been listed as a direct threat to the US for the last three years due to its role in fighting terrorist groups. That assessment has clearly shifted as Hezbollah is being leveraged as part of the plan to isolate Iran. We are also likely to see greater US efforts to enforce decisions on Hezbollah and more calls on the militant group to disarm.

These changes in the US’ approach comes at a time where the activity in Syria is reducing, so Hezbollah is increasingly turning its attention back to Lebanon. Over recent years there have been reports that Hezbollah’s weaponization has peaked, including technologically. They have definitely suffered a significant level of casualties both in manpower and financially.

Hezbollah has also seen a shift in the level of support from their key supporter base, including areas that were generally regarded as social incubators for their movement. Yet they have been improving tactically and the soldiers and members they do have are battle hardened and have much more experience than previously from their extensive activities in Syria.

Even though Hezbollah may be facing serious political, social and financial challenges, it is still a serious and well-organized opponent to both the US and Israel. Hezbollah’s main strategy will continue to be based on raising the cost of war on Israel and trying to shift the battle lines south towards the upper Galilee.

It appears we are seeing the anticipatory phase before an inevitable confrontation, as Israel is not willing to accept the increasing threats that Hezbollah represents. Seizing the US strategy of isolating Iran, a fragile Syria and the consensus that many Arab states share on the issue of weakening Hezbollah. All of this suggests that the coming months might bring some attention’s shift from Syria to its neighboring countries.

Over recent months there have been questions about how Jordan has been invulnerable to any serious terrorist attacks, especially after the battles of Mosul and Raqqa. While there are many reasons why Jordan has not had a serious attack, there are also many signs that Jordan like any other country is not invulnerable and is indeed under real threat.

The Russo-American cooperation in the south of Syria has been a major factor in containing the threat of ISIS and protecting Jordan’s borders. However, the major security challenges Jordan faces are internal.

While on the surface the economy is the major challenge in Jordan, the underlying challenge is the lack of clear vision for the future of the country. If we compare Jordan’s development plans in the 1950s and 60s where we had national plans across major sectors, a well functioning bureaucracy and the creation of major institutions such as the University of Jordan, the Hussein Medical Center as well as radio and TV and sport city.

We have seen other major projects in more recent years, but we appear to have lost the national spirit and reinforcing national identity that comes with them. As part of this Jordanians have lost the feeling that their government represents them and that citizen dignity and respect is the priority of the system of government.

The loss of these sentiments is one of the major sources of discontent in Jordan. There is no denying that the socio-economic situation in Jordan represent big part of the problem, but the lack of narrative and clear direction for the future means people feel lost and confused.

In the absence of a national identity narrative, this vacuum is being filled by religious narratives that make people belong more and more to the past, making it more difficult to integrate and react positively to the present.

What Jordan needs today is a change in the political class, not in personnel, but how leaders and bureaucrats are thinking. Policies and plans should start thinking of collective efforts to achieve future goals. Jordanians need to discover their history to understand the value that their land represents and this would be the first step toward the change in mentality, behavior and how they interact with society.

Unfortunately, the policies of recent years have accumulated power in the hands of an inner circle in Amman, where most of the cities in Jordan have paid the price of being neglected at all levels. The main challenge today is how to reengage the youth so they feel they are part of this country, making them protagonists of change and development not antagonists of society. This cannot happen if the same people continue with the same approach, narratives and lack of vision that dominate the political scene at the moment.

A few months ago when Saudi Arabia and other Gulf countries took a stand against Qatar, it was clear that the crisis is not a short term one. The countries involved have a long history of conflict with Qatar, including recent attempts to influence their policies.

While it is unlikely to be a short-term crisis, there is little suggestion of the potential for military escalation. Rather, it is more likely the next steps will be an escalation of economic and jurisdictional measures against Qatar.

In recent weeks the Qatari Foreign Minister has visited major global capital cities to speak with his counterparts who could influence international decision-making on the issue. The strategy is to demonstrate the Qatari willingness to negotiate on the key issues and to defend themselves against accusations of sponsoring and supporting terrorism.

Also under discussion is likely to have been the potential deepening of Qatari relations with Iran, which goes against the demands of the Gulf States. It is distinctly possible that this is already moving as indicated by events in Syria. Some believe that the recent progress of the Syrian Army and its allies on the ground are a result of the new Qatari position with Iran.

While relations with Iran are a useful political leverage point for Doha, it could easily backfire. Qatar’s strategy is heavily reliant on the US to step in to defend it; deeper relations with Iran are unlikely to lead down a path where the US protects it. Qatar has signed a MOU with the US to support the fight against terrorism; the current US administration may well interpret that to include Iran.

The US appears to be eager to contain the gulf crisis, despite the fact that the Trump administration’s containment plan for Iran is based on increasing pressure and isolation. As such, it will be interesting to watch how Doha pivots back to the US and distance itself from Iran in order to resolve the Gulf crisis.

Qatar’s other ally in Turkey is also struggling both in Syria and within its own borders. The US-Kurdish alliance is causing issues, enough for the Turkish President to publicly criticize its establishment quite bluntly, but to no avail. Internal Turkish politics are heating up with growth in support for opposition parties, internal fragmentation and increased security concerns.

What we are seeing is that Qatar’s two strongest supporters in the Gulf crisis in Iran and Turkey are unlikely to be able to maintain their positions in the longer term. Qatar’s best option is to position with the US as an impartial broker, however that will likely require Doha to accept a large part of the demands from its Gulf neighbors.

Any successful de-radicalization strategy requires an understanding of the nature of the problem and anticipation of the risks. It is it not an easy mission to comprehend the level of challenge unless there is, in the mind of the state, a long term vision with clear ideas about the model of the future Jordan.

Even with a solid approach, it is a difficult task. Frankly, we do not have strong de-radicalization narratives; instead we rely on the insufficient strategy of moderate clerics countering radical narratives. Without serious concrete changes in policies, communication and socio-economic development, this is unlikely to make a difference.

This is not a religious battle, but rather it is a battle of existence, of life and death, where people should be integrated into the present rather than being prisoners of the past. We need to make people feel positive about life, being productive and appreciating their existence. A comprehensive plan is essential, otherwise we are treading water towards failure.

Many would argue that radicalization is not the primary issue in Jordan, and that we just need to minimize the risk of violence and terrorist attacks. While we don’t have frequent terrorist attacks or major incidents at the moment, this kind of complacency will only lead to one outcome.

Radicalization is not only measured by security outcomes. The latent evolution of the phenomenon should be analyzed with a progressive methodology. If the current situation in many Jordanian villages and cities continues, radicalization will grow and in order for the state and its institutions to reflect societies positions, then policies and programs will adopt these radical tendencies.

These radical thoughts and approach will quickly spread through the security and military establishment as most recruits come from these villages and cities. Many would argue that the model we have is not radical, but the definition of radical will shift with the mentality of the people. The risk is when people reach the point where their attitudes, social behaviors, and thoughts are unconsciously radical, the state moves with them and radicalism is normalized.

The major challenge is, understanding the deep cultural problem of radicalism. We need a serious political will for change so we can hope to have smart minds to predict the problems and future implications through a serious diagnosis of the problem across all sectors of the population. Radicalization is not limited to school curricula or religious narratives. It needs to be at the top of the agenda for national security, from the revision of the security system, the state communication strategy and the socio-economic process. While it is a long process, a concerted and serious effort is required now to ensure that outcomes are achieved in the long-term.

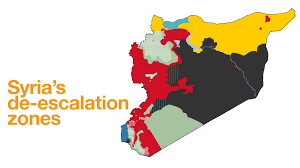

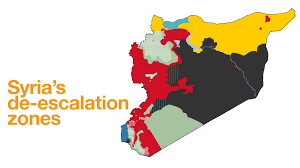

The recent policy to implement de-escalation zones, where Syria is divided into separate areas where different groups are based, is the first concrete steps toward saving the cease-fire and imposing stability in Syria on the pathway to ending to the conflict.

The broader impact of the Gulf crisis is currently being felt in Syria as well. Several experts have commented that since the boiling over of tensions with Qatar there has been increased confusion among the fighting groups in Syria.

This confusion is working to the advantage of the Syrian army as they recapture territories that they previously controlled. Multiple public sources are reporting a significant decline in military activity across Syria, including Idlib, Deir Al Azour, Joubar, and even Daraa.

The confusion also provides opportunity for exploitation from other players in the conflict. Turkey’s ambiguous position suggests they are eager to have a role in any agreements to exert control in the north of Syria and manage the risk its faces from the US-Kurdish alliance.

The interest from Turkey provoked Iranian involvement, which was demonstrated by Iranian missiles fired into Syria. Clearly, Iran will resist any attempts to diminish its influence in the conflict and any reconstituting of a new government. Continued Iranian involvement will then guarantee greater and ongoing interest from Israel, which has also been launching attacks and raids against Syrian military posts.

The fighting in Syria has always been complicated, and is the current front for ongoing regional tensions and conflicts. The policy of de-escalation zones is a potential source of stabilization and eventual ceasefire. However, for this to be a success, greater international efforts are required where countries not currently engaged in the conflict, and those that do not have a clear alternate regional agenda step in.

The current regional players in Syria are using it as a battleground for their underlying conflicts, which clearly does not align with the objective of stability. The new de-escalation zones policy creates separate geographies where countries in the region can play a role in guaranteeing success, but must be directed under the umbrella of the international community.

We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. If you continue to use this site we will assume that you are happy with it.Ok